Canada has a business competitiveness problem.

We have low productivity and innovation rates, leading to suppressed worker incomes relative to the United States. We have a low private investment rate, resulting in less creation and adoption of technologies.

Now, with new tax and regulatory reforms rolling out in the U.S., 2018 confronts Canada with a new competitiveness challenge. Money will flow south when investors feel Canada is no longer comparatively hospitable to investment.

As Minister of Finance Bill Morneau points out

in FP Comment today, business investment finally picked up in 2017 with a positive growth rate, especially in the last two quarters. But a few quarters do not make a trend, even though strong U.S. economic growth helps us as well. Statistics Canada reports that private investment intentions are expected to decline in 2018 from 2017Our current level of business investment— $336.5 billion (in 2007 dollars) — is lower than business investment for every quarter going back to mid-2012. Intellectual property investment, at $29.3 billion at the end of 2017, is the lowest since 2005, except during the recessionary crisis of 2008-09, when it was comparable.

It is great that Amazon has announced it will be creating 3,000 jobs in Vancouver. However, because of Canada’s inferior salaries, tech workers in Vancouver annually earn an average of US$60,000 (Toronto is only slightly better at US$61,000). In Seattle, Boston and New York, Amazon workers are paid over US$100,000. In U.S. cities, the labour market is only getting tighter. Many Vancouver tech graduates have trouble finding jobs so they have to take what they can get.

Offering discounted worker salaries is not a way for Canada to be competitive. Nor is offering a discounted dollar. Competitiveness is attained when businesses want to come to Canada to compete internationally, even when our salaries and our dollar are high. That competitiveness comes through investment and innovation —and this is our challenge.

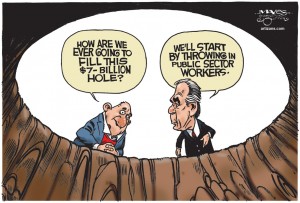

For growth, we need to be most concerned about private sector investment (see the accompanying graph). Going back to the 1990s, Canada’s private investment rates were quite low, a bit more than 10 per cent of GDP. As economist Pierre Fortin noted many years ago, it was also a period in which growth in output per working hour was miserable: the fourth lowest in the OECD.

After 2000, private investment improved remarkably, rising to almost 13 per cent of GDP. No doubt the commodity boom led to more investment, but so did tax reform. What we often forget is that tax reform was especially geared to reduce taxes on services, as manufacturing already enjoyed a low corporate tax rate. Thus, it is no surprise that the most important impact of tax reform was on investments in the service sector, which virtually doubled as a share of GDP (manufacturing’s share, however, declined). This was in contrast to Australia’s experience, where, without tax reform, both manufacturing and service investments declined as a share of GDP during its commodity boom.

While tax reform after 2000 helped our investment performance, that began to fall apart after 2012 as taxes began to rise. Canadian private investment as a share of GDP from 2012–16 was lower than most other OECD countries, especially in service sectors.

It is often claimed by the left — and is unfortunately publicly repeated by the Minister of Finance — that Canada’s reforms to our business taxes had no effect on investment. Not only does this undermine most credible international scholarly studies (including an excellent paper published by Finance Canada). It also goes against experience.

Our business tax reforms created an important competitiveness advantage for Canada. We offered a much lower tax on capital compared to the United States. It also helped offset our three biggest natural disadvantages: a small market, widely dispersed across vast geography, in a cold climate. Low capital taxes made up for the extra burdens of energy and labour required to move goods and services.

All that has changed. Canada no longer has a capital tax advantage, now that the U.S. has slashed its rate as part of its sweeping reform package. The U.S. average federal-state corporate tax rate is now one point below Canada’s (26 versus 27 per cent), but some important competing states like Ohio, Texas and Washington don’t even have a corporate income tax at the state level. Texas now has a corporate tax rate advantage over Alberta of six points.

Meanwhile, companies that would have looked to Canada first to locate their marketing and intellectual property assets over the last two decades will now turn to the U.S. instead, with an American corporate tax rate of 18 per cent on such “intangible” income, one-third less than Canada’s corporate tax rate.

The Canadian tax burden weighs 10-per-cent heavier on new investments than it does in the U.S., at 21 per cent here versus 18.9 per cent there. With higher energy and labour taxes, Canada now offers a distinct tax disadvantage for businesses to compete here.

Unfortunately, the collapse of our former tax advantage is only one of the problems that have handicapped Canada’s competitiveness. Our regulatory environment is becoming infamous for its unpredictability and hostility to new projects. We are slow in approving new infrastructure. We have let environmental policies choke off resource development. We cannot get our most valuable export to tidewater. And this is all happening, with fresh snafus every few days, just as the U.S. is enthusiastically dismantling investment-killing regulations in energy, finance, agriculture and other sectors.

The first step to fixing Canada’s competitiveness problem is admitting that we have one. Many businesses are already in the process of relocating capital and functions out of Canada and into the United States. If we insist on sitting on our hands in denial, a low dollar and sinking salaries will end up being all the competitiveness we can offer.

Jack Mintz is the president’s fellow at the University of Calgary’s School of Public Policy.