Australian Cardinal George Pell, the most senior Vatican official to be charged in the Catholic Church sex abuse crisis, must stand trial on charges alleging he sexually abused multiple victims decades ago, a magistrate ruled Tuesday.

Magistrate Belinda Wallington dismissed around half the charges that had been heard in the four-week preliminary hearing in Melbourne but decided the prosecution’s case was strong enough for the remainder to warrant a trial by jury. The number of charges has not been made public

When she asked Pell how he pleaded, the cardinal said in a firm voice, “Not guilty.”

Wallington gave the 76-year-old permission not to stand, which is customary.

When the magistrate left the room at the end of the hearing, many people in the packed public gallery broke into applause.

- Cardinal’s alleged sex abuse victims testify in Australian court

- Pope apologizes to sex abuse victims, but defends Chilean bishop

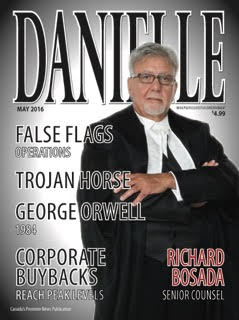

Pell’s plea marked the only words he spoke in public. Wearing a cleric’s collar, white shirt and dark suit, he was silent as he entered and left the downtown courthouse with his lawyer Robert Richter. More than 40 uniformed police officers maintained order on the crowded sidewalk outside.

The cardinal’s legal team found some solace in the outcome, with Richter telling the magistrate “the most vile allegations” had been dismissed.

Lawyers for Australia’s highest-ranking Catholic had argued that all the accusations were untrue, could not be proved and should be dismissed.

Pope Francis receives a cricket bat from Pell at the Vatican in October 2015. The case places both the cardinal and the Pope in potentially perilous territory. (L’Osservatore Romano via AP)

Wallington dismissed one charge because the alleged victim was an “unsatisfactory witness” during the first two weeks of the preliminary hearing, when complainants testified via a video link from a remote location to a courtroom closed to the public and media.

“It is difficult to see how a jury could convict on the evidence of man who has said on his affirmation that he cannot recall what he said a minute ago,” Wallington said.

“In my view, this is one of those rare cases where the witness demonstrated such a cavalier attitude toward giving his evidence that a jury couldn’t rely upon it,” she added.

She described her job in the preliminary hearing as “sifting the wheat from the chaff.”

“Unless the credibility of a witness is effectively destroyed, credibility and reliability are matters for a jury,” she said. “Where the evidence is so weak that the prospect of conviction is minimal, it is not of sufficient weight to commit” a defendant to stand trial.

She said she did not dismiss charges “merely because there is a reasonable hypothesis consistent with innocence.”

Ordered to remain in the country

She ordered Pell, Pope Francis’ former finance minister, to appear on Wednesday in the Victoria state County Court where he will eventually stand trial.

Under his bail conditions, Pell cannot leave Australia, contact prosecution witnesses and he must give police 24-hours notice of any change of address.

Pell was charged last June with sexually abusing multiple people in his Australian home state of Victoria. The details of the allegations against the cleric have yet to be released to the public, though police have described the charges as “historical” sexual assault offences — meaning the crimes allegedly occurred decades ago.

Richter, Pell’s lawyer, told Wallington in his final submissions two weeks ago that the complainants might have testified against one of the church’s most powerful men to punish him for failing to act against abuse by clerics.

But prosecutor Mark Gibson told the magistrate there was no evidence to back Richter’s theory that Pell had been targeted over the church’s failings.

Since Pell returned to Australia from the Vatican in July, he has lived in Sydney and flown to Melbourne for his court hearings. His circumstances are far removed from the years he spent as the high-profile and polarizing archbishop of Melbourne and later Sydney before his promotion to Rome in 2014.

The case places both the cardinal and the pope in potentially perilous territory. For Pell, the charges are a threat to his freedom, his reputation and his career. For Francis, they are a threat to his credibility, given he famously promised a “zero tolerance” policy for sex abuse in the church.

Advocates for abuse victims have long railed against Francis’ decision to appoint Pell to the high-ranking position in the first place. At the time of his promotion, Pell was already facing allegations that he had mishandled cases of clergy abuse during his time leading the church in Melbourne and Sydney, Australia’s largest cities.

So far, Francis has withheld judgment of Pell, saying he wants to wait for justice to run its course. And he did not force the cardinal to resign, though Pell took an immediate leave of absence so he could return to Australia to fight the charges. Pell said he intends to continue his work as a prefect of the church’s economy ministry once the case is resolved.

- Why this Chilean abuse survivor refuses to accept Pope Francis’s apology

In recent years, Pell’s actions as archbishop came under particular scrutiny by a government-authorized investigation into how the Catholic Church and other institutions have responded to the sexual abuse of children.

Australia’s Royal Commission Into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse — the nation’s highest form of inquiry — revealed last year that seven per cent of Catholic priests were accused of sexually abusing children in Australia over the past several decades.

In testimony to the commission in 2016, Pell conceded that he had made mistakes by often believing priests over people who said they had been abused. And he vowed to help end a rash of suicides that has plagued abuse victims in his hometown of Ballarat.

Pell testified to the inquiry in a video link from the Vatican about his time as a priest and bishop in Australia. He did not attend in person because of a heart condition and other medical problems.

Police said at the preliminary hearing that they had planned to arrest Pell for questioning had he returned to Australia in early 2016 to testify.

His lawyers argued in court that Pell was targeted for “special treatment” by detectives from a police task force that investigated historical sex abuse. Police witnesses denied that accusation.

The investigation of Pell began in 2013 before any complainant had come forward to police, whom Richter accused of running “a get Pell operation.”

Pell’s lawyers told the court in February that the first complainant approached police in 2015, 40 years after the alleged crimes, in response to media reports about the royal commission.

Pell was charged by summons in Rome and agreed to return to Australia to face the allegations.